EMO:SFT Overview

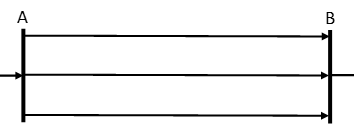

The principle behind SFT is simple: if one circuit in the grid has an unplanned outage, then every other line in the grid could then become overloaded. Therefore we need to limit the flow on some circuits just in case there is an outage. For example, the figure shows a portion of a grid where three identical circuits are in parallel between nodes A and B, so the total power flow is divided equally across the three. If one circuit trips, then the other two will each end up carrying 50% more power than they did prior to the trip. Under an SFT approach, each circuit would have two constraints each looking like

Flow in protected circuit + 0.5 × flow in contingent circuit ≤ Capacity

where there is one constraint for each of the other two circuits. For example, if each circuit carries 100 MW, then after one circuit trips the remaining lines will each carry 150 MW. If the circuit capacity is 150 MW, then the constraints would be Flow in protected circuit + 0.5 × flow in contingent circuit ≤ 300.

So in principle, the SFT process:

- outages each and every circuit in turn;

- for each circuit outaged, check the loading on every other circuit;

- formulate constraints to protect any circuits that are overload.

In practice, circuits on the grid typically have more capacity than is apparent, because their respective capacity ratings are based on steady-state operation, whereas after a circuit trips the SO re-dispatches the market during the 15 minute off-load time, during which time a lot can change. In steady state, the thermal capacity rating of a circuit is determined by how much it sags due to it being heated as power flows through it: there are statutory limits on the distance between transmission circuits and the ground, or objects on the ground (trees, etc). Lines lengthen as they heat due to power flowing in them (and due to changes in ambient conditions) which is why they sag.

If a circuit is already loaded at its capacity rating, then it is assumed to be at maximum allowable sag and therefore the simple approach above applies. But, if a line is running below its capacity rating, then if it suddenly carries more power due to the tripping of another line, it will take some minutes before the additional heat produces additional sag: for this reason, the SFT constraints can typically allow a circuit to be loaded higher after another circuit trips than might be expected.